Funny Trying to Figure Out Male and Female Bathroom

The genius behind stick figure toilet signs

We use them every day without thinking about them, but the universally recognised symbols for male and female toilet signs have much more going on than it seems. Jonathan Glancey explores the enduring appeal of these quaint but powerful pictograms.

S

Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey is a magnificent and serious film, sparkling intermittently with surprising and knowing humour even about the lowly toilet. When the character Dr Heywood Floyd, chairman of the National Council of Astronautics, is caught short on board his Pan-Am space flight from the United States to a giant orbital space station, he is faced with a sign warning "Zero Gravity Toilet: Passengers are advised to read instructions before use". There follows a list of 10 inscrutable instructions spanning 700-odd words; it would take an average person four minutes to read these out loud. In space, no one can hear you scream in frustration.

What is funny here is that a simple, natural human function is held up by the hyper-rational demands of highly sophisticated 21st Century technology; and that despite all this brilliant technology humans are reminded several times a day of their inescapable Earthly nature. It also shows that even in such high-tech times, some decidedly low-tech answers are still difficult to beat. And one of the most simple and elegant of these is the male and female figures used for toilet signs.

In 2001: A Space Odyssey, mankind meddles with this humble design classic (MGM)

The last thing anyone wants, on Earth as in space, is to be faced with a baffling lavatory. And, yet, even today signs for public lavatories can introduce frustrating confusion at times of the most urgent need. Cyrillic signs, like those found in Russian-speaking countries and some Balkans nations, will almost inevitably bewilder the vast majority of world travellers, as will traditional Chinese and Japanese pictograms.

In Poland, meanwhile, you can come across lavatories indicating "gents" with a triangle and "ladies" with a circle, while in Lithuania men are represented by an inverted pyramid and women by a pyramid standing the right way up. While such signs might be obvious to Russians, Chinese, Japanese, Poles and Lithuanians, how many Americans, Indonesians, Germans, Kenyans or Peruvians would know which way to turn?

Conditioned response

The best, if not the most entertaining, signs for lavatories are those depicting a paper cut out-style man and a woman in the most basic form. Used worldwide, the male figure is much like a classic gingerbread man, while the female figure is different only because she wears a dress. While there are many women who rarely if ever wear skirts, every woman and every man understands the image. These characters are pretty much those sketched in an unreflecting instant by children from Asia across the Americas to Europe. This may well be a response conditioned by customs and imagery exported from dominant nations that have taken root in societies worldwide over generations; whatever the case, the imagery clearly works.

Even in cultures where women do not wear short dresses, it is hard to confuse the symbols (Getty Images)

These primal images are, in fact, archetypes, which is why they have been very useful in the design of universally understood pictograms for lavatories; such archetypal imagery also informs the design of a plethora of signs found, for example, in international airports and major railway stations: for restaurants, cafes, bars, lifts, escalators and so on. They are understood intuitively. No words need accompany them. And, if they did need to, then semantic confusion is likely to follow.

In the English language alone, there are very many words not just for lavatory – toilet, WC and restroom – but also for men and women. Until recently, public lavatories in Britain were signed "Ladies" and "Gentlemen". Today, when there are arguably few "Ladies" in the old-fashioned sense and traditional "Gentlemen" are all but extinct, these have been replaced with "Men" and "Women", or by pictograms.

Elegant information

The ascent of the pictogram makes sense. It requires no language skills, either foreign or indigenous. It is self-explanatory. Public lavatory pictograms are surely one of the most widely accepted and successful examples of intuitive design. If all public design was so very rational and obvious, life, of course, might be less fun than it is when confronted with and happily challenged by signs that make us smile, or laugh at with a mix of embarrassment and guilt.

All too many Westerners have found public signs translated from Chinese to English awkwardly funny, and both amateur and professional photographers have had a field day with them. Equally, there is something rather noble in the way successive generations of designers have aimed at making universally intelligible signs both instantly informative and elegant things in their own right.

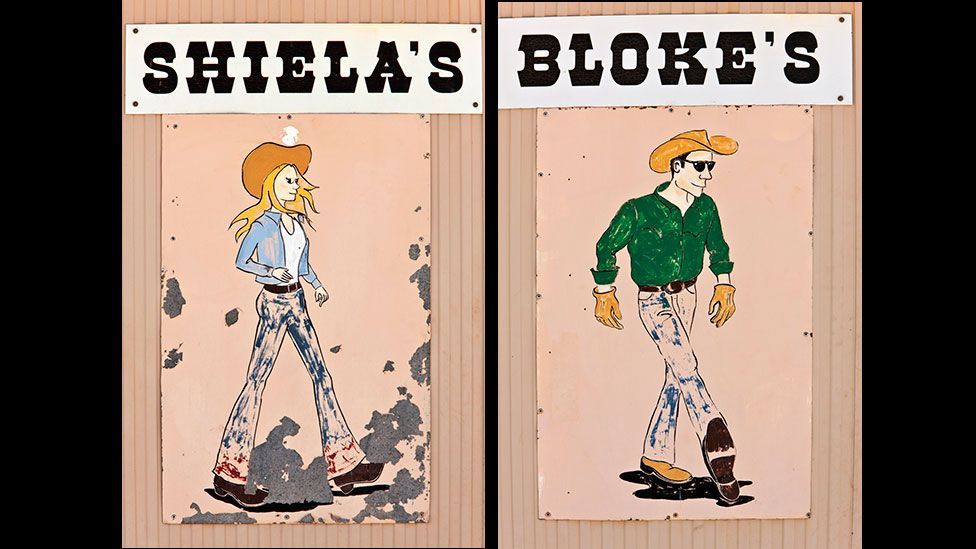

In Australia's Northern Territory, the pictogram has taken on a thoroughly casual Antipoedan appearance (Getty Images)

Such signs, though, go beyond conventional notions of design; they are part of something both more primal and scientific. Just as science, or biochemistry, explains why we are wired to take notice of red signs and to stop at red lights, so we respond intuitively to very basic images indicating men and women's toilets. These can be designed well – as in most airports and railway stations – or badly, or even entertainingly, but our brain responds to them reflexively, or intuitively.

Classics of design

One of the best early examples of intuitive global signs for public lavatories was that created for British Rail in the mid-1960s. As part of a major modernisation programme, the state railway was given a new and all-embracing corporate identity by DRU [Design Research Unit], a design studio founded by Marcus Brumwell and Misha Black in 1943. Working with Margaret Calvert and Jock Kinneir, who designed a distinctive Rail Alphabet typeface based on Helvetica, DRU devised a clean-cut and convincingly modern aesthetic that was applied to all locomotives, trains, stations, published material and, yes, signs for lavatories.

When words enter the scene, the symbols' power can be diminished (Getty Images)

In the 1970s, the British example was developed on a more comprehensive basis in the United States. In 1974, the US Department of Transportation commissioned the American Institute of Graphic Arts to create a set of pictograms to be used throughout public transport networks whether road, rail, air or sea. Working with Cook and Shanosky Associates, the Institute produced 34 signs – there are now 50 in use today – identifying elevators, escalators, babies' changing rooms and public lavatories in ways that remain crystal clear 40 years on. Like British Rail's 1964 corporate identity the US Department of Transportation signage system is widely regarded as a classic of modern design.

That warning sign on the door of the spaceliner toilet in 2001 may have been designed to amuse cinema audiences, but it also shows how much thought has gone into the design of signs for public lavatories: a universal need has needed universal signage. And, no matter how amusing the more wayward, exotic and downright incomprehensible toilet signs can be, it is a relief to pretty much everyone to know where to go without having to ask or even to think for more than a precious second or two.

Have you seen any toilet signs that have caught your eye - for better or worse? Head over to our Facebook or Google+ page, or message us on Twitter, and let us know.

mullinssubbillson.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20140911-the-genius-of-toilet-signs

0 Response to "Funny Trying to Figure Out Male and Female Bathroom"

Post a Comment